If you would like to support this work, in the spirit of generosity, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

At this moment, I am turning to the resources that I am already grounded in and seeking out resources from voices I trust. I continue to use dharma as a guiding tool in which to move through the world, language and communication as a means of building relationships, and interdependence as a method of acknowledging that though I might not have the exact roadmap for how we get there, my liberation is inextricably tied with yours.

Social Change Ecosystem

I am a student of the Social Change Ecosystem Map. The Social Change Ecosystem Map is a framework that helps individuals, networks or organizations align with social change values, individual roles and the broader ecosystem. Some of us are Frontline Responders. We take on the urgency of rapid response, are able to be in the thick of the crisis, we gather resources for the protest. Others are Healers, tending to the trauma caused by oppressive systems, institutions, policies and practices. Rarely am I a Frontliner Responder. Most often I am a Healer, showing up for my communities to provide care through meditation contemplation and dharma.

What’s most important to understand about this ecosystem is 1) We often toggle between different roles 2) We cannot hold all of the various ecosystem roles at once and 3) The various roles we hold allow us to build a stronger coalition toward long-term change.

Today, I join you as a Weaver. We see the through-lines of connectivity between people, places, organizations, ideas and movements. We bring communities together for dialogue and connection, focusing on understanding our shared histories and values and fostering solidarity.

I want to tell you about my personal history of land-back. What this can look like and what it means for a generation and how this is helping me understand the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

A Very Brief History of Kenyan Colonization, Mau Mau and Settlement Schemes.

In short. I would not be in the United States if the British had not returned land to the Kenyan people.

When the British came to Kenya in the late 1890s - early 1900s, colonial masters that they were, they chased the indigenous people away from their homes and took the best land for themselves. The people resisted. The Warrior Otenyo led a battalion of Gusii warriors (Kisii, my family’s tribe) in resisting British colonialization. In the past year, I’ve been mystified by this image of him. If you look close, you’ll see a faint glow of horns extending from his temples. I haven’t found an explanation for this.

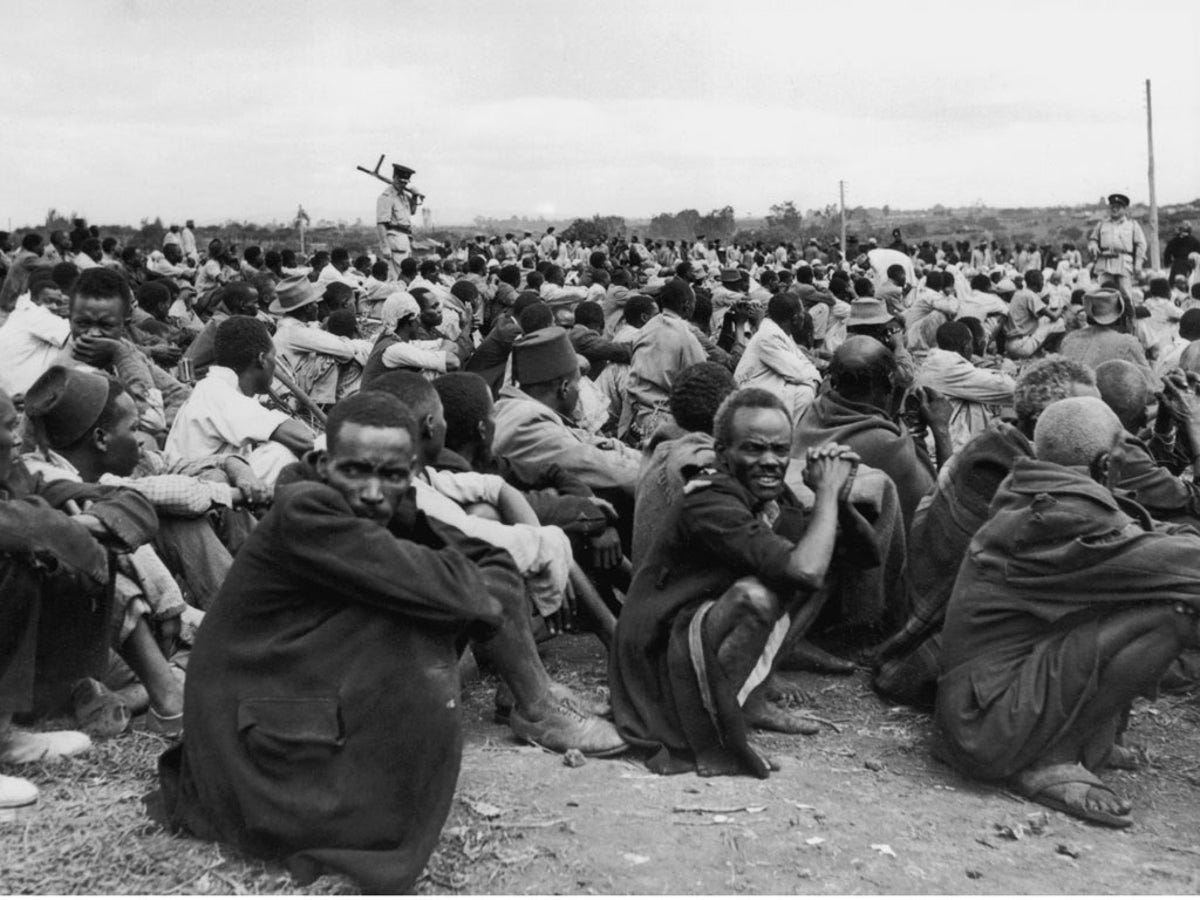

The British stayed in Kenya for the duration of the “Scramble for Africa” the broader period in which European nations were colonizing Africa and plundering its riches. To share directly from my father “There were people there. They took the land that Africans were living on and took them to reserves, land reserved for “natives”. They even used forced labor. If they said that they wanted you to work for them, you had to.”

They took the land. The most fertile land. They took the land and assigned it to British settlers. The British liked Kenya best because of the temperate climate. It wasn’t too cool or too hot. This was most of the highlands of Kenya (Nakura, Eldoret, Nairobi, Mount Kenya).

The Kisii weren’t quite moved from where they lived but in general, you couldn’t own land where you wanted. My paternal family, the Masese Clan, were not uprooted from their ancestral home but we were made to work on the reserves. My grandfather, Anderson, had to do “required” forced labor. It meant that he went to work for the mzungu (white man) on their farms. After working for some time, he was allowed to go home. You couldn’t say no.

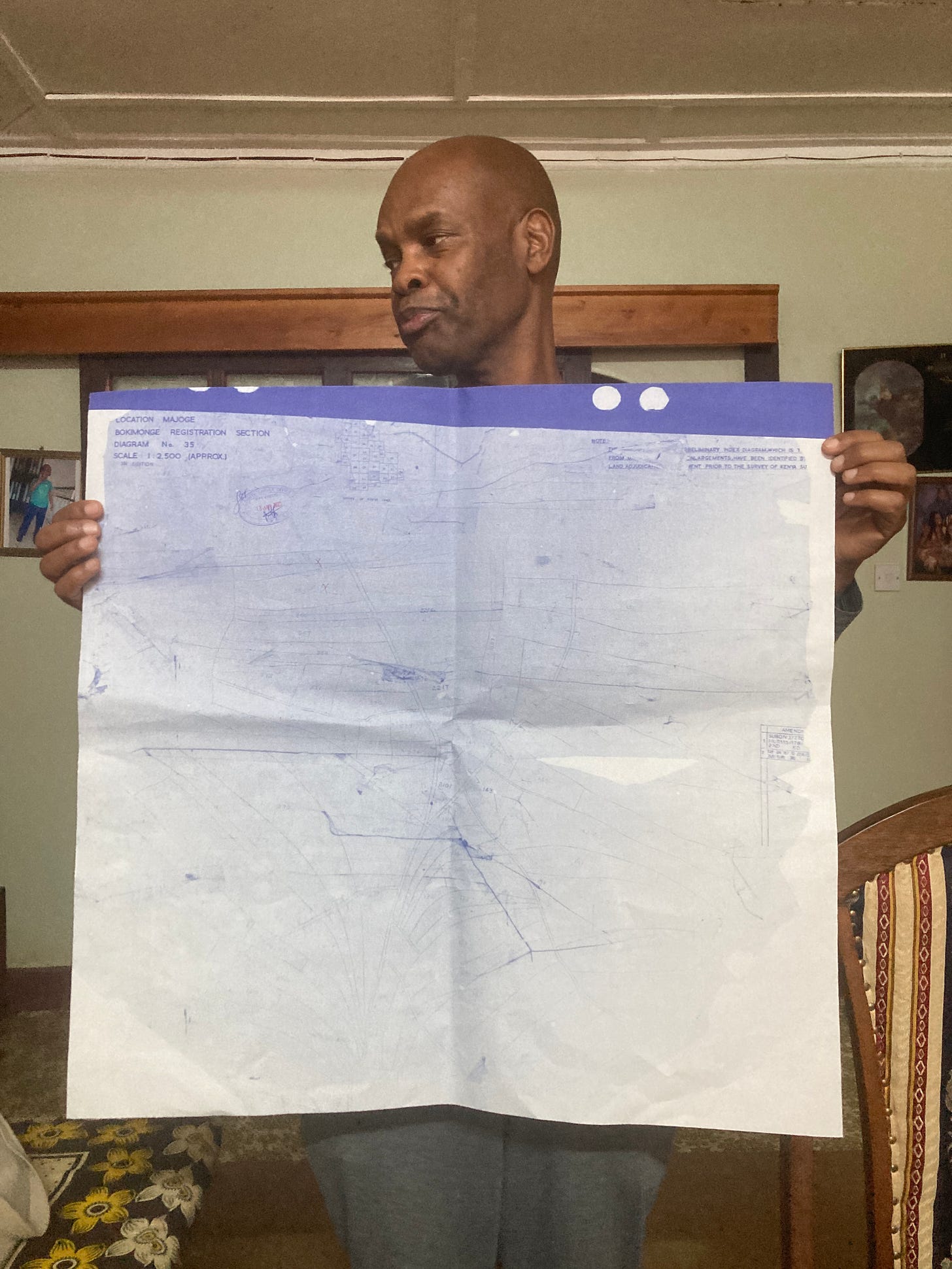

The Mau Mau Rebellion from 1952–1960 signaled a period of Kenyan resistance to British colonial authorities. Kenyan Independence was won on December 12, 1963 (Jamhuri Day), and the British set about resettling people who were packed in the reserves. Enter “schemes.” The British and newly independent Keyans negotiated a resettlement of the nyakua, land that had been grabbed. Schemes offered land to those who had been displaced in the struggles against British colonial rule.1 Kenyans had to “buy back” the land. They applied for and were awarded grants that were then meant to be used to buy off the white settlers from the land they were occupying.

The local Kisii administrators (chiefs) talked to locals about filling out the forms to get their land. There was a lot of mistrust. People couldn’t believe that the mzungu would leave the land. My family, both my paternal and maternal, were amongst the Kisii who took the chance. On my father’s side, in 1964 the Angimas moved to the land we now call home. And to quote my father once more, “It changed our lives forever. We wouldn’t be anything we are today if we hadn’t received this land.” On this fertile land, we tilled the soil, planted seeds, and reaped the benefits of rich harvests. We built homes, built mills, and bought cattle which paid for school. My parents’ generation are among the first to leave the village, to receive a formal education, to go to university and to immigrate to the United States.

Convoluted though it may have been (fuck having to apply for a grant for your own land), my life as it exists today doesn’t happen if Kenyans don’t receive their land back.

Solidarity.

My history is my starting point for understanding the Israeli occupation. Self-determination is a personal value rooted in my recent past and guiding me toward an understanding of Palestinian statehood. I claim this solidarity with all oppressed people all over the globe. I would go so far as claiming this with all living beings, the worms and leaves among us. This is as much as I know and I am learning and listening.

I’m currently reading the Genjo Koan as a part of Brooklyn Zen Center’s Fall Ango. Last week in dharma shares, we contemplated how not knowing is one of the most intimate experiences we can have. This especially spoke to me. 👇

When you first seek dharma, you imagine you are far away from its environs. But dharma is already correctly transmitted; you are immediately your original self.

-Genjo Koan

If we embrace the non-duality of both not knowing and immediately being our original self, how can we open up space for service and action? Where does not knowing propel us to learn and better inhabit the dharma of interdependence? In this view, not knowing is a launching point, the beginning of study, which is ultimately a return to self.

May we all find a way to return to self. May this return to self then open up space for action.

xo Jessica

SOME RESOURCES

The Social Change Ecosystem by Deepa Iyer

Decolonizing Non-violent Communication by Meenadchi

We Begin Here: Poems for Palestine and Lebanon edited by Kamal Boullata & Kathy Engel (For the rest of October, Interlink will be donating 30% of your purchases to Middle East Children’s Alliance (MECA) for food, hygiene supplies, water, and fuel for hospital generators in Gaza.)

Hanif Abdurraqib on Palestine, Islamophobia & Manufacturing Consent

Inner Fields Sangha. The next sangha gathering will take place over Zoom on Sunday, Nov. 5, from 6-8p EST. This gathering will explore the relationship between grief and anger in the face of injustice and oppression, and ways of letting grief arise and move through us so that our actions/ activism are wisely rooted in compassion. I hope to be there and you should join too.

Studying Our Ecosystem.

Are you interested in studying the Social Change Ecosystem? I want to explore this space with others and think about how we inhabit our roles locally, and how this fractals out in solidarity with global movements against oppression. I imagine this will be a loosely facilitated space for study, discussion and collaboration.

Comment below or reach out to me directly if you’re interested! TBD on whether this will be in-person (Brooklyn) or online.

Join The Laundromat Project’s 2023 People-Powered Challenge.

Join The Laundromat Project’s 2023 People-Powered Challenge. This annual peer-to-peer fundraising campaign organizes the collective power of the people. Your participation is vital to support initiatives like our residency for community-attuned creative projects by artists of color based in Bed-Stuy, grants for local artists to create projects for the community, our fellowship for artists across the City who are interested in developing a socially engaged creative practice and a diverse range of community programs like sidewalk workshops and public activations. Be part of this incredible community resource campaign from October 23rd - November 1st.

✨ I love the Laundromat Project dearly and your support makes an impact. ✨

Learn more and donate here. 👉🏾 https://bit.ly/2023PPWR

Work with me.

You can find me weekly at Heal Haus, five days a week at Arena and often at 462 Halsey Community Farm.

🌞

“Promised Land: Settlement Schemes in Kenya, 1962 to 2016”. Catherine Boone, Fibian Lukalo, Sandra F. Joireman

So powerful, J. Thank you for sharing these stories and the thoughts they bring about now.